VOS.VOSBitmapIndexing

Advances in Virtuoso RDF Triple Storage (Bitmap Indexing)

Orri Erling (Program Manager - OpenLink Virtuoso)

October 31, 2006

Abstract

This paper describes the use of bitmap indices for optimizing Storage of RDF triples. Implementation techniques are described and results analyzed for different size data sets, up to a billion triples.

We show how we can load the 1 billion triple LUBM benchmark set with a sustained rate of 12692 triples/s and the 47M triple Wikipedia data set at a rate of 20800 triples/s.

Updates

Since the previous version, we have split the IRI ID-to-IRI mapping into two tables, one for the prefix and one for the local part of the name. This drops per triple space usage from 92 to 74 bytes after the LUBM load. We have also somewhat changed the distribution of operations on threads, dropping the load time from 28:45 to 23:446 (HH:MM).

Introduction

Persistent RDF data needs to be indexed in at least two ways: One way for retrieving the properties of a subject and another way for locating subjects which have a given property set to a given value. We may safely say that all RDF storage schemes will face these requirements. How a specific storage scheme addresses grouping triples into graphs will vary depending on the expected number and size of graphs. For a general purpose solution that is not tuned to any specific data set, the graph information will have to figure on each triple. Creating distinct tables for graphs can be inconvenient if there are many small graphs, thus this is not a good general solution even though this makes good sense when a specific graph is expected to grow very large.

We will address fine-tuning storage schemes for specific data sets in another paper., here we will be concerned with a general purpose scheme.

As soon as we move past a few million triples on a typical desktop machine, we are likely to exceed available memory and processing will quickly become IO bound. Hence space efficiency of triple storage is a prime concern.

We will present results obtained with Virtuoso using different triple storage models and introduce a bitmap index scheme that brings significant improvement to both load and query times.

The data will be periodically updated as the loading process is further fine tuned.

In the below, we abbreviate subject as S, predicate as P, graph as G and object as O.

Test Data

We have used two different size data sets for testing: The medium size set is the Wikipedia links data set with 47 million triples. As the large set, we have used the Lehigh University Benchmark 8000 university data set with 1 billion triples.

The initial impetus for the present work came from loading the Wikipedia links data set. Using a 3GHzAMD 64 machine with 2G RAM, we found that the loading was heavily IO bound. The database was striped over 4 SATA disks and disk activity was at 350% at the end of the load, meaning that 3.5 of 4 disks were busy at any time. The load took 11 hours to complete. We have reduced this to 2h 50 minutes by using a more space efficient indexing scheme.

RDF Workloads

We see the typical RDF usage scenario to be similar to that of a text based search engine. The incoming data stream is a bulk load of documents and the query load is basically random access with fairly uneven distribution of search terms.

We can imagine other types of workloads such as business intelligence with complex queries making statistics over a large fraction of the store or update intensive OLTP workloads but we feel that a purely relational solution for these remains fundamentally better. Thus, if such content is to be presented as RDF, it is best done in the context of Virtuoso by using Linked Data Views where SPARQL becomes SQL accessing the native relational data in Virtuoso or any external database.

We note that the trend in business intelligence databasing is towards column-wise storage, i.e. having any given column of a table stored next to the same column of the next row of the table. This makes sense since most queries do not address all columns of the table, thus it is advantageous to only read the columns that are actually referenced. The RDF storage model is not so different: For example, for calculating the average trading price of a commodity over millions of transaction records, if these were stored as RDF triples, it would be possible to read a contiguous range of the PGOS index with P and G fixed and add up the prices and count the rows, which is not so different from how a column-wise stored database operates. In fact, if PGOS has a bitmap for S and there were not many distinct Os, the storage efficiency would be even better than what one would get for column wise storage, as we shall later see. So there are actually cases where a triple storage model can do some aggregation operations quite efficiently. This bears further research.

Looking at the bulk load situation, we notice that most inserting is basically in ascending order, creating new IRIs for new subjects. The index from predicate/object value to the subject has a more random access pattern, still there too we find that within each distinct GPO the S will often be ascending.

Multithreading and Multiprocessing

Bulk load of RDF data must be divided across a number of threads so that IO load can be distributed over multiple concurrently operating disks. This poses no transactional problems since a document does not have to be loaded as a single transaction. On the other hand, if transactional load of data is important, multiple document loads may proceed concurrently. This is however liable to deadlock and in the case of inserting new subjects, the threads are likely to wait for each other. The situation occurs when a thread inserting many adjacent GSPO tuples upgrades row locks to a page lock and the new subject would come to the same page. Of course, lock escalation can be disabled but there is little gain an having two threads competing for the same page even if they each run on a different processor. Experience rather indicates that in such situations, two processors perform worse than a single processor, even when measured in real time.

Thus our loading model works with one stream of documents, where each document is split over 4 threads: The first for parsing the TTL or RDFXML and allocating IRI IDs for the IRIs and 3 threads for inserting triples. These three worker threads feed off a queue that is filled by the parser thread.

This distributes read requests on the PGOS index quite evenly but leaves the threads often getting in each other's way when updating the last page of GSPO.

Thus, a more optimal setting could be to have one thread take care of all purely ascending inserts on GSPO. Most of the time an index lookup will not even be necessary since the data will come to the same page as the previous insert.

If a GSPO tuple is not in the same sequence, it can be inserted by a separate thread. Thus a better solution might be to have one thread for parsing, one for ascending inserts of GSPO and 3 sharing all non-ascending GSPO and PGOS tuples. Relatively more threads should be used for PGOS since there is a higher chance of IO being needed.

Experiment shows that contention on mutexes on a multiprocessor system is several times more expensive than on a single processor. Differences between OS are significant but even the better performing ones such as Solaris have a high cost for any mutex wait. Spin locks are available on some systems as a distinct object from the mutex but these have such a prohibitive worst case that they are not generally usable for serializing database index operations. The main critical section that we are interested in is the one that controls transit from an index page to another. This serializes the read/write lock of the page being left, the hash table for looking up the buffer for the destination page and the read write lock for the destination page. Each index tree has its own mutex for the purpose. The typical section consists of resetting the write flag of the former page, getting the buffer of the target page and setting its write flag. This is less machine instructions than locking and unlocking the mutex. Experiment shows that 3 threads writing to the RDF table collectively spend 10% in the mutex of the GSPO index and 20% in the PGOS index's mutex. Still, the small number of waits makes this benefit little from multiple CPUs. Past two threads, performance does not increase on our test system running Linux FC5. One solution would be to automatically range partition trees into approximately equal size chunks and give each of these their own tree and own mutex. While the section is short and may possibly be shortened still, only 10 threads on the same tree will cause spinlocks to hit a very bad worst case, thus spin locks are not an option even though these are often slightly faster. Also, there are longer stretches where this mutex is taken, for example when rehashing a hash table or when getting multiple pages for compaction, thus a spin lock that does not automatically upgrade to mutex is not acceptable.

Using Bitmap Indices

Bitmap indices are a well established relational database technique for dealing with low cardinality key values. Examples of such are gender, the state/country part of an address, generally any enumeration type value where the count of distinct values is small compared to the row count of the table. After each key value comes a bitmap where the bit corresponding to the row number of the row where the value occurs is set. We note that such a scheme requires that each row of the table have an integer or at any rate integer-like row id. More generally, we can say that bitmap indices are suited for representing any key whose last key part is an integer and where the leading parts are not by themselves unique.

Thus, the PGOS index is a candidate for bitmap index representation since S is an IRI ID, thus a special kind of integer. The GSPO index is not a candidate for this, since O is an ANY type value that cannot be easily mapped into the set of integers. Some storage schemes assign an integer id for each distinct O however. In such situations, the O could be a bitmap but this would have benefit only in the case of a bag of triples sharing the same GSP.

Experiment shows that for the 47M triples of the Wikipedia links set, there are about 8M distinct PGOs. Thus, if the S were a bitmap, there would be on the average a little under 6 bits set in each bitmap. Of course, the values are not evenly distributed. Thus, about 6M PGOs have only one S and the most popular PGO has about 2M Ss.

Thus, for a bitmap index to be useful, it must have a minimal overhead for bitmaps with only a single bit set and it must be rapidly searchable for random lookups and inserts.

In Virtuoso we resolved this by making a bitmap index have the same layout as a general index with one variable length string that does not participate in the key order comparison attached at the end.

Thus, the key for PGOS has two integers, one string, one integer as the ruling part and one string as dependent part. If there is only one bit set, the bitmap string is empty and the S holds the value of the bit. If more than one bits are set, the S is rounded to the lower 8K below the lowest value and the bits are represented in the bitmap string,. The bitmapstring uses different representations depending on how many bits are set. In the RDF case, the bits that are set can be very sparsely spread out, more so than in a relational database with an enumeration for state, country or other category field. Thus, if each bitmap index entry had a fixed range, we could easily lose any space advantage. Thus we divide the set of signed 64 bit integer values into segments of 8K values. When there is at least one bit set in such a range on values, there is a compression unit corresponding to this range stored in the index. Many compression units can fit into a single bitmap string, as long as the bitmap string itself stays under 1 KB. When the bitmap string would become longer, we simply split it, somewhat like splitting a B tree leaf. The longest possible compression unit is 1KB long, with 1 bit per each of the 8192 values in the unit's range.

We have not used any dictionary based compression because this takes time and is not searchable for random access. Thus, if a compression entry (CE) has only one bit, it is a 4 byte offset of the S of the containing index entry. If it has under 512 bits on, it is an array of 16 bit bit numbers from the start of the CE's range and a 32 bit offset from the S of the containing row. If it has more than 512 bits set, the bitmap is represented as a 1KB bitmap with no compression.

Using the WordNet? data set, where there are 1.1M distinct PGOs for 1.9M triples, the bitmap index for PGOS took 60% of the space of the non-bitmap index for GSPO. Using the Wikipedia and the LUBM data sets, the bitmap index was about a quarter of the size of the GSPO index.

The insert operation into a bitmap index is somewhat more complex than with a regular B tree. Still, with the task of loading the 1.9 M triples of WordNet?, the time difference was only 4% in favor of regular indices. With any larger data set, bitmap indices were found overwhelmingly superior because of fitting four times more data into the same working set.

While the logic for bitmap indices is quite a bit more complex than for a regular B tree, the most often traversed execution paths are not much longer plus there is a likelihood of better CPU cache utilization and a certainty of better disk performance due to more compact data size.

Other Compaction Measures

We have considered the possibility of leaving out leading key parts in some indices, after all, the PG sequence , is almost always the same throughout the page. However,, if PGOS is bitmapped, the typical page will not contain so many rows, thus benefits are not huge. The GS sequence is also repeated a large number of times in a GSPO index page. The index entry is typically 25 bytes, with 6 overhead, 3 times 4 for IRIs of G, S, P and an average of 7 for the O. If repeating GS were compressed away, there would have to be an entry in their place indicating where the original value was so that the page could still be read in random order. Thus maybe 4 of 27 bytes could be saved. Making a dedicated table per graph gets the same gain without the complexity.

The table mapping IRI IDs to the IRI string and back can benefit from compressing namespaces of qualified names.

The most effective and generally applicable measure that we have tried is opportunistically merging adjacent stretches of dirty index leaf pages before writing to disk. This results in index pages that are 25 to 30% fuller than without and applies to any application that makes large inserts or updates. The overhead of having such optimization done before preparing a batch of dirty pages to be written to disk is only 4% of real time with the RDF loader. With an application performing inserts only, the overhead is still under 10%. These overheads are measured when the working set would fit in memory even without the compaction. Of course, all overhead turns into net gain if the working set would otherwise exceed the size of RAM. If the working set is much below the size of RAM, the compaction never runs because pages are not prepared for paging to disk anyhow. This is far better than any algorithm linking tree maintenance to updating the tree. Since this is basically an IO optimization, it is best done in relation to IO. Some improvements to the compaction algorithm are possible, such as not limiting the operation to stretches of contiguous dirty pages but also writing clean ones if the end result does not have more dirty pages than the starting situation.

This same operation is also ideally suited for reassigning disk pages so that logically contiguous leaves become physically contiguous. More experimentation is needed there. Even with a read ahead system that sorts by disk position and uses distinct threads for reading distinct devices, tighter locality can make a radical difference, over 10x in real time. For purely random access situations, the disk layout is not so significant.

Results and Test System

This section presents the results of loading the LUBM 8000 university data set and the 47M triple Wikipedia links data set.

The system used was a Supermicro 7045 SATA server running Linux FC 5 64 bit with 4 disks and 8G memory and two Intel Xeon 5130 processors at 2GHz.

The Virtuoso server was the regular open source version 4.5, revision 5, generally available as of November 2006.

The server was compiled with -O, normal optimizations.

Compiling with -O3 instead was tested to produce a 5% drop in real time for the CPU bound Wikipedia load.

The database files were each in separate ext2 file systems.

O_DIRECT was used for bypassing OS file cache but we do not think this made a significant impact on the results.

Load Times

Loading the data took 23 hours 46 minutes of real time, with a CPU time of 35h 39m.

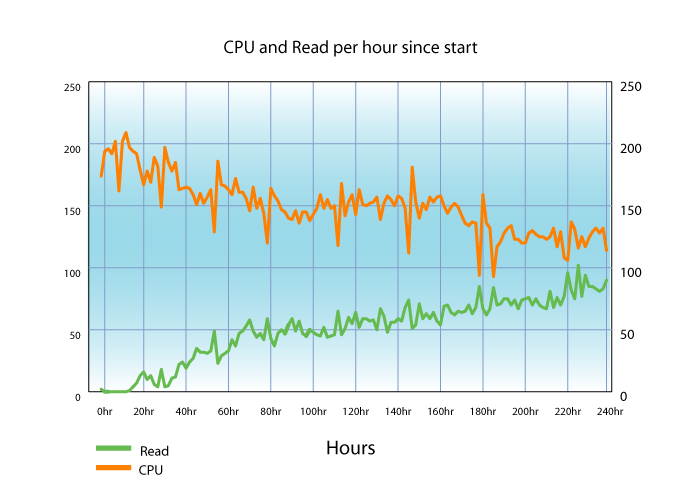

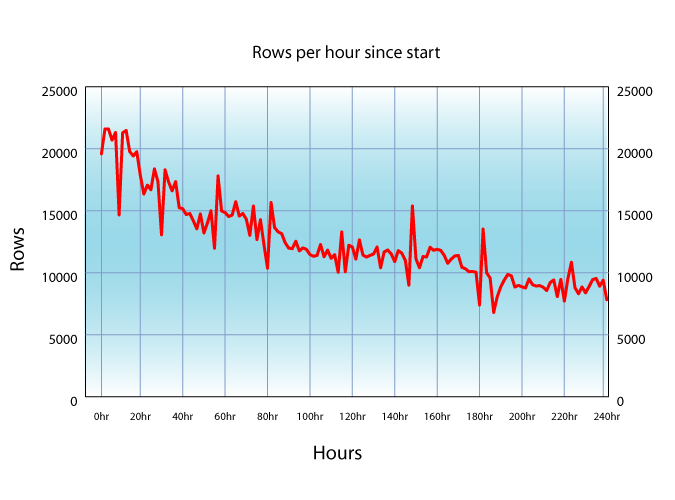

The below graphs show the throughput in triples per second and the disk read and CPU percentages as a function of time. In the percentages, 100 means one CPU or one disk constantly busy. The samples were taken at 10 minute intervals.

The throughput dips periodically as the database makes a checkpoint, i.e. writes all dirty pages to disk and makes a clean read-only state and discards the transaction log. AFTER each checkpoint the throughput rises slightly due to better working set. The server was set up to keep about 3/4ths of the buffers dirty in the expectation that a dirty page would be updated many times before it moved out of the working set.

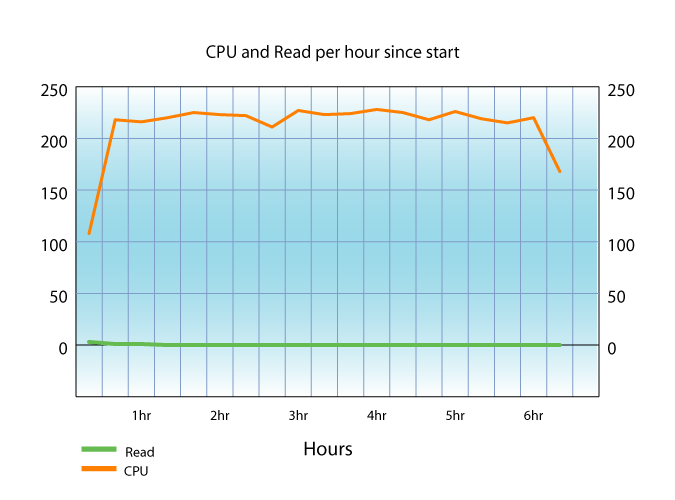

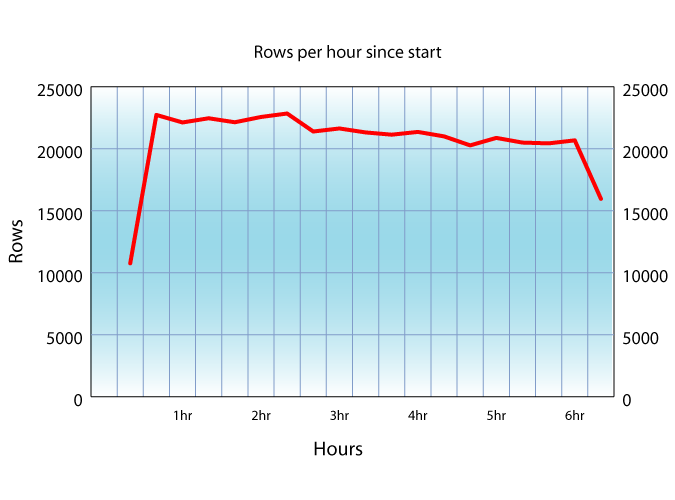

In order to measure the effect of a large database size on load times of mid-size data sets, we loaded the 47M triple Wikipedia set on top of the 8000 university set, going to the same tables but with its own graph.

The load of the Wikipedia TTL file took 28 minutes 26 seconds or real time and 67 minutes of CPU.

The below graph shows the insert rate and CPU load. There is no IO worth mentioning, the operation takes place in memory.

We note that the throughput at the start is almost twice that of the lUBM load, even though the LUBM load started with an empty database and this one goes on top of 1 billion triples.

This is due to the Wikipedia data being in TTL, which is a much more efficient format than RDFXML. The CPU utilization is much better since the parser can now feed triples into the insert queue faster than the insert worker threads can insert them.

Data Sizes

The 8000 university data set produces a database with 76091 MB of space used. The database files are striped on 4 disks, with a preallocated database size of 120G. The server is configured with 5468 MB of database buffers out of a total system memory of 8G. The data set consists of 1068M quads, all in the same graph. the space consumed per quad is 75 bytes after the load is completed.

We note that this comes in large part from having half full pages that were not compacted by the automatic compaction.

We note that this comes in large part from having half full pages that were not compacted by the automatic compaction. Running a manual compact command drops this size to ***

During the load, there were 2.35M disk reads, i.e. database cache misses, of which 1.75 M were on the bitmap index for PGOS. There were 0.55 M disk reads for the index for long O values, i.e. values that are not inlined in the quad table's O column. We note that the disk seek times were quite long towards the end, due to data being spread far apart in relatively long database files, 30G each. The average disk read was 17 ms while with smaller databases it is about 10 ms, presumably due to less disk head movement. Using more disks decreases this latency. There were 14.8 M disk writes, for a volume of 115625 MB written. Thus some pages were written to several times but most were written just once.

The sizes for the different indices were as follows:

| Size in mB | Table | Index |

|---|---|---|

| 37645 | RDF_QUAD | RDF_QUAD |

| 10343 | RDF_QUAD | RDF_QUAD_PGOS |

| 7379 | RDF_IRI | RDF_IRI |

| 7155 | RDF_IRI | DB_DBA_RDF_IRI_UNQC_RI_ID |

| 6869 | RDF_OBJ | RO_VAL |

| 6041 | RDF_OBJ | RDF_OBJ |

| 10 | RDF_PREFIX | RDF_PREFIX |

| 9 | RDF_PREFIX | DB_DBA_RDF_PREFIX_UNQC_RP_ID |

To see how much space is lost due to partly filled pages, we ran an explicit compaction on the RDF_QUAD_PGOS index.

The size dropped from 10324 MB to 9129 MB.

This suggests that for mostly read intensive data sets it is worthwhile to run an extra compaction pass after large bulk loads.

The compaction took 3.5 hours but this is a background activity that does not interfere with other operation, except insofar it loads IO and bias the working set.

The data set had 173M distinct IRIs.

This fits well in the range of a 32 bit IRI ID.

We note that the RDF_QUAD table count is not limited by any 32 bit row id since it does not have any row id to begin with.

Using a 64 bit IRI ID is possible but it would simply make the tables larger.

The GSPO index would be about 60% bigger, the bitmap index for PGOS would be affected less.

Query Implications

We will later publish our analysis of running the LUBM queries on Virtuoso at different scales. For now, we can make the following general comments.

For queries where multiple predicates of the same subject are specified, the bitmap index for PGOS works specially well.

The join of all posts having the sioc:topic "database" and sioc:topic "sparql" for example becomes a logical and of bitmaps for these plus the bitmap for Ss with a sioc:type of sioc:Post.

This can typically be resolved in a few disk reads, one for the first page of "database" topics , first page of "sparql" topics and then the page of sioc:Post types that has the lowest S gotten from the AND of the sparql and database topic bitmaps.

The time complexity is logarithmic for finding the first and linear for the rest of the merge intersection or bitwise AND.

This however presupposes that the type information is explicitly represented.

It could be that the sioc:Post type is not explicitly given but should instead be inferred as the union of blog posts and wiki pages, for example.

This would substitute the sioc:Post bitmap with a logical OR or merge union of multiple other bitmaps.

The same techniques remain otherwise applicable.

For traversing data from object to subject, such as listing all subforums and posts of a forum, the GSPO index will work well, in log(n) time for each first post or subforum and then linear for subsequent ones.

Certain inferencing situations will require knowledge of subpredicates.

For example, has_finger could be a subpredicate of has_part.

If only the most specific parthood is explicit, unions will have to be generated from the subpredicates if querying for a higher level predicate.

If querying for what the relation between <me> and <my left index finger> is, we should get has_finger and has_part.

We may support type subsumption and subpredicates at the SQL engine level.

Instead of generating complex unions that are quite difficult to optimize, we may have the SQL execution graph node have specific knowledge.

Thus, when querying with a given G, P = rdfs:type and O = sioc:Post and S being retrieved, we could expand the search to merge all known subclasses of sioc:Post into one stream of results.

This would work also if the predicate were known only at run time.

Data about cardinality of types can quite easily be incorporated into the query cost model if necessary.

For conjunctive queries, i,e, queries where the graph is left unspecified so that any triple from any graph will join with any other graph if the conditions on S, P and O match, we notice that indices including the graph as key part are ineffective. Thus it is possible to take the table with GSPO and create indices in the order of SPOG and POSG. The G can be a bitmap in both cases but this is of little benefit unless the same triple is present in multiple graphs. Simply making indices with SPO and POS does not allow efficient deleting if multiple graphs assert the same triple. Removing one triple should check if the same triple is in other graphs which is time consuming. It is however not impossible since it is possible to relatively quickly enumerate distinct graphs based on the GSPO index: Just take the first row and then the first row with G greater than the previous one. This is log (n) times the number of distinct Gs for each deletion, still quite impractical, specially if there are many Gs and few repeated triples.

The ideas presented above are speculative and may or may not be implemented. The first point of call is an analysis of the LUBM query load plus some typical queries against the SIOC and FOAF schemas against data harvested from the web.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that it is possible to load a billion triples with relatively even performance throughout the load with common server hardware. There are many ways of further optimizing the loading. Even now, performance is quite adequate for even large data sets.

We note that RDFXML is significantly slower to load than TTL. Measurement shows that this is not so much due to syntax but to the fact of the LUBM data being in 160000 small files whereas the Wikipedia is one big file. The IRI IDs are cached during the load so that we get a better hit rate with bigger files.

Anyway, we will next change the IRI to ID mapping and drop the LUBM database size by 12G and optimize the IRI ID lookup transaction. We will update the results when this is done, still in Nov 2006.

We believe we have found a scalable and efficient triple storage scheme, thus future work can concentrate on optimizing queries and improving the mapping of relational data into RDF.

This paper will be updated as results improve, either by configuration changes or further optimizations.

Further work on storage optimization is possible through specializing the storage format, for example by introducing SPMJVs, subject-predicate matrix join views. This will be later revisited in the context of relational to RDF mapping.

References

- LUBM publications

- Oracle on SPMJVs

- SWAD-E Web Storage & Retrieval workshop - Alberto Reggiori